While learning vocabulary, I keep bumping into vocabs that could be translated as “situation”. It’s either Japanese has a lot of vocabs for “situation” or I’m starting to have an early signs of dementia and I’m glad that it’s the former. So what are they and do all of those really have the same meaning?

After some digging, turns out the answer is yes and no. Yes when we’re translating from Japanese to English, but no when going the opposite direction.

Let me list them out:

- 状況 (joukyou) – General circumstances or current state of affairs

現在の状況は複雑です → “The current situation is complicated.” - 事情 (jijou) – Personal circumstances, often involving complications or reasons

家族の事情で帰国しました → “I returned home due to family situation.” - 場合 (baai) – A specific case or instance, “in the situation where…”

この場合はどうしますか → “What do you do in this situation?” - 場面 (bamen) – A scene or particular moment/setting in a situation

気まずい場面でした → “It was an awkward situation.” - 局面 (kyokumen) – A critical phase or turning point in a situation

新しい局面に入った → “We’ve entered a new situation.” - 様子 (yousu) – The appearance or observable state of a situation

様子を見ましょう → “Let’s see how the situation develops.” - 有様 (arisama) – The deplorable state of things (usually negative situations)

ひどい有様だった → “It was a terrible situation.”

So we can see that Japanese is incredibly specific, one English word translates into seven different Japanese words depending on context. This tendency to be hyper-specific extends to their vocabulary in ways that completely defy my instincts as a non-Japanese speaker.

When Japanese Refused to Just Combine Words

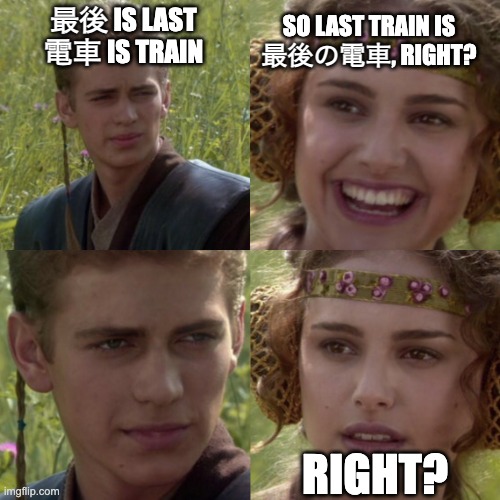

For example, when I want to say “last train,” I immediately think of combining “last” and “train”. Both have direct translations in Japanese: 最後 (last – saigo) and 電車 (train – densha). So logically it should be 最後の電車

Japanese speakers will definitely understand it, but it’s not natural in daily conversation, and they can smell from miles away that you’re a 外人 (foreigner) because the common way to say it is 終電 (shuuden).

Some of you with keen eyes might notice this word takes one kanji from each component and guess the reading is “goden” (go from saigo and den from densha). But again, you’re wrong. It’s shuuden. Why? Maybe I’ll explain in another post.

More examples of this pattern:

- 入社 (nyuusha) = “joining a company” (not some combination with 会社)

- 食後 (shokugo) = “after eating/after a meal” (not 食事の後)

- 小鳥 (kotori) = “small bird” (not 小さい鳥)

It’s like Japanese looks at important concepts and says, “This deserves its own word, not just a description.”

The Plot Twist: When One Word Means Everything

Now here’s where it gets really fun. We’ve established that Japanese is super specific, right? Well, enter 多義語 (tagigo – polysemy), which is just a fancy way to say one word can have multiple meanings. And when I say multiple, I mean multiple:

- 気 has 12 meanings (not counting established set phrase) which has the basic idea of “spirit”

- 差す has 16 meanings with the core concept of “distinction” (I guess, I’m not sure. What do I know?)

- 取る has 18 meanings with the core concept of “taking”

- 掛ける has, to my surprise and furrowing eyebrows 25 MEANINGS with the core concept of “I don’t know, I give up trying to grasp the meaning of this word with my meager knowledge”

So Japanese forces you to choose between seven words for “situation,” creates special unified words for “last train,” then turns around and makes 掛ける mean literally everything depending on context.

Welcome to the vocabulary paradox: too much precision and too little precision, all at the same time. And somehow, it all makes perfect sense to Japanese speakers.

Look, I’m not going to pretend this is some beautiful linguistic feature that I’ve learned to appreciate. It’s exhausting. Every time I think I’ve figured out a pattern, Japanese throws another curveball. Just when I get comfortable with the idea that Japanese loves precision, boom! here’s 掛ける with 25 different meanings that somehow all make sense to native speakers but leave me scratching my head.

But here’s what I’ve realized: getting frustrated with Japanese vocabulary is like getting mad at water for being wet. This is just how the language works. Japanese speakers aren’t trying to make life difficult for learners, they’re just operating on completely different assumptions about how language should organize meaning.

So yeah, I’m still tired, still frustrated, and still confused about why 掛ける needs to mean everything under the sun. But at least now I know I’m not going crazy when I encounter the 47th different word that translates to “situation.”

And maybe that’s progress enough for now.

Leave a comment